- Home

- Rolonda Watts

Destiny Lingers Page 2

Destiny Lingers Read online

Page 2

I peek into the mirror and find myself dressed in my conservative navy blue Ann Taylor pantsuit, starched white blouse, my sapphire blue-faced Rolex watch (a graduation gift from Daddy), and Mother’s white pearl necklace and matching earrings—I don’t even remember getting dressed. And while I may be ready for work, I am not quite readied for life. Particularly not the life I may find after this day.

The thought of taking the A train to Rockefeller Center is more of an intrusion than I can handle on this particular morning. So instead, I call a local gypsy cab, since Yellow Cabs aren’t as readily found cruising the streets of Harlem. The dispatcher answers in a deep, husky Dominican accent and then, in a loud, booming voice, assures me that the cab will arrive in fifteen minutes.

As I wait, I stare out of my big bay window. The glorious vision of my elderly neighbors’ flower boxes fills my eyes with tears, and my vision blurs as I lose sight of Garrett and me together, filling flower boxes at that age. I quickly remind myself that I cannot cry. I cannot afford to have swollen eyes on the six o’clock news. No time for any kind of emotional baggage today. I have ignored all signs up to this point. One more day won’t hurt.

The harsh blast of the gypsy cab’s horn startles me back into reality. The impatient cab driver lays on his horn again and again. I curse him as I grab my Coach leather satchel and reporter’s notebook and dash out the door. Whatever I am feeling—whatever I am going through—it will have to wait; it’s time to put on my game face and get to work.

I double-lock our front door and dash down the stairs. I am shocked when I see what looks like a souped-up pimp-mobile waiting on the street before me. I am almost embarrassed to ride to work in this shiny-rimmed, baby blue, horn-blaring vehicle. The driver, with a big, thick black mustache, ducks his head below the gaudy white tassels dangling from his side window and looks up at me with a glare of impatience.

I slip down the steps and into his big car. It smells like Opium perfume.

The cabby barrels down the avenue in a mad, reckless race to beat the lights. Between the earsplitting blasts of salsa music and his loud radio transmissions in Spanish, I can barely hear myself think. The gypsy cab plows its way downtown, dodging potholes and early-morning pedestrians. I look out of the smudged window and see New York City carrying on her business as usual.

With a quick turn, the cabby makes a dramatic swerve up to the curb of 30 Rockefeller Plaza and screeches to a halt underneath the awning. The cabby has the nerve to overcharge me, but I am too distraught to argue, and I let him slide this time. He hands me a makeshift business card—as if I’d call his lame ass again. I grab my stuff and slide out of the cab.

I make my way through the revolving door and to the elevator that will take me to the fourth-floor newsroom. An overly nice security guard, clad in his gray uniform, greets me at the elevator bank with his usual big smile and a warm “Good morning!”

I wonder if he can tell my heart is broken.

The newsroom is bustling this bright spring morning as reporters congregate around the assignment desk, hungry for a meaty assignment. Tom Mack, the grouchy assignment editor, is busy barking out marching orders to crews scattered around the city, gathering news.

I grab a New York Times, the Post, the Daily News, and a USA Today and slip into my cubicle, hoping to dodge Tom’s hawk eye. He probably has one of those dreadful rookie assignments cooked up for me—another hospital teddy bear drive? Another Good Samaritan award? Or another subway delay? The big, juicy lead stories of murder, mayhem, scandals, and politics are usually saved for the news veterans or Tom’s favorites. Today, I am neither.

It seems it’ll take an act of God for a big story to finally land in my lap. The only lead story consuming me today seems to be that of my own life.

Who else knows about this? What will I do? When did it start? Where do I turn? Why didn’t I speak up when I got the first inklings long ago?

I want to call my mom, cry on her shoulder, and feel the sacred comfort of motherly advice, but I know that’s not what I’d get if I called home. I know Mother and Daddy’ll join forces and in unison chime: “We told you so.”

My folks have despised Garrett from the first day they met him. They were not at all happy about my even talking about marriage at twenty-one, much less to Garrett Nelson, whom they found arrogant, rude, and downright shady. They wouldn’t be at all surprised if Garrett hurt me.

“That Garrett is just so full of his wee little self!” Mother has been on an anti-Garrett campaign ever since he basically told her and Daddy to mind their own business and butt out of our marriage. To my folks, Garrett might as well have told them to go to hell.

All of this family drama still comes as a tremendous shock to me. I thought for sure my folks would love Garrett. After all, he came from “good stock.” The Nelsons were featured on the cover of a major national white magazine back in the 1950s as one of the first black families to integrate the upper-middle-class, traditionally white Shaker Heights community of Ohio. Garrett’s dad was a lawyer and his mom a schoolteacher, who baked big, fat Virginia hams just so her three beautiful black preppy sons could have fresh ham-and-cheese sandwiches with homemade potato chips after their football practices.

His little sister was my age and the only black girl I ever knew named Jenny. She was a daddy’s girl who spoke in a baby voice and craved constant attention. Jenny would have normally gotten on my last nerve—in fact, under any other circumstance, I would have just downright despised the girl—but I desperately wanted to be a part of her family. So I bit my lip, behaved myself, and worked harder to get along.

The Nelsons were a beautiful family. Garrett’s dad adored me and would spend hours holding court in the kitchen of their ranch-style suburban home, acting out his latest joke or sharing another one of his many golf adventures. He would have me doubled over with laughter, while Mrs. Nelson smiled on, her gregarious husband’s stories getting longer and more elaborate with each telling.

Thanksgiving at the Nelson home was amazing. As many as thirty family members lovingly gathered around one long, exquisitely set table full of delicious food, including as many as three turkeys—and of course, a nice, fat, honey-baked ham. I was amazed at how much unconditional love, laughter, joy, and unyielding support was around that table. When Garrett and I announced our engagement, they all clapped and whooped and hollered. They jumped up and down. They hugged and kissed us and told us how happy they were. I never ever wanted to lose that feeling of unconditional love and acceptance. Not ever.

Yet on this bright spring morning, I apparently have.

It’s nine in the morning, and Garrett will be getting off the ABC news desk soon. We have to talk—today. I cannot pretend any longer. I pick up my work phone, fingers trembling and cold, and begin punching in Garrett’s number, nervous and still not sure what to say.

“Yeah, Nelson.” His abrupt I-am-very-busy-and-even-more-important news voice snares the phone.

“Garrett?” My voice does not sound like my own.

“Hey, baby, what’s up?”

I feel like an interruption. “I … we … we need to talk, Garrett. Can we talk when I get home?”

“What’s wrong?”

I can’t get the words out of my mouth. It hurts too much to speak. “We just need to talk.” There’s silence on the other end of the phone. “Are you there?” I ask.

“Yeah … I’m still here … I’ll see if I can go in late tonight so I can spend some time with you, okay?”

“I’d appreciate that, Garrett.”

We sound like two people who don’t even know each other, not the loving couple we used to be. Not the two people who met the first day of journalism school in 1980 and watched their close friendship and deep admiration and respect for each other blossom into a passionate and bona fide love. I sit here today, five years later, wondering where all that love has gone.

“I’ll see what I can do.” Garrett’s voice drops. “Call you later.” And with that, my husband is gone. I wonder just how far gone he really is.

“Hey! You!” I am startled by a loud, barking “Tom the assignment editor,” now standing over my desk, pointing his fat finger at me. My heart pounds furiously as he urgently rattles out orders like bullets.

“I’ll call you back, baby,” I say into a dead phone. “Yeah, Tom. What’s up?”

“We got a hostage situation developing up in Harlem. That’s your neighborhood, isn’t it? Perp’s holding a kid, maybe three or four years old. He says he’ll kill him unless he gets to talk to a reporter. You’re all I got right now. Need you to hightail it up there and check it out.” Tom turns and heads back to his assignment desk, marching as if off to war. “If it’s something, it’s yours!” Tom yells over his shoulder as he flips on the radio mike to find out the estimated time of arrival of the closest camera crew.

Cameraman Fred Robinson and his audio guy, Butch Mason, say their ETA is seven minutes.

“Where the hell is my reporter?” Tom yells like an animal at me across the newsroom. “Let’s move!” He emphasizes the order with a Jackie Gleason swerve of the neck.

I grab my papers, my Coach satchel, my reporter’s notebook, and my Mont Blanc pen and am out the door.

I guess I’ll have to put off meeting with Garrett until later. After all, this big, breaking story could be the big “get” of my budding career—with a live shot for the five, six, and eleven o’clock newscasts, advancing my visibility and credibility in the number-one news market. I’ll spend the night preparing video packages for the early morning news and perhaps even a network news break-in.

Forget the story of my life right now.

Again, my life will have to wait.

Thank God for my career.

Chapter Two

By the time I make it down the elevator and out to the Fiftieth Street awning, I can see the Channel 4 news van accelerating up the street. I can also hear the pulsating boom-diddy-boom-diddy-boom of reggae music blasting out the window as my news crew gets closer. Cameraman Fred and his soundman, Butch, are both bobbing their heads to the funky Caribbean beat but are also looking very serious behind their dark shades. Fred swerves up to the curb with immediacy as Butch jumps out and slides open the news van’s roaring door and helps me hop in.

“Sounds like we’re going to be up there a while,” a concerned Butch reports. “Cops’ve been negotiating with this guy for more than three hours now and looks like he’s not lettin’ up.”

“Yeah,” Fred chimes in from the driver’s seat. “They say the guy’s pissed off ’cause the city took his kids. Now, why he thinks holdin’ his kid hostage is going to help his case with the city, I do not know.”

“Yeah, that fool could actually kill his kid on the six o’clock news.” Butch blows a swift puff of air through his lips and props his big, booted foot up on the dashboard with a thud. “People are nuts today, ya know?”

“Tell me about it,” I reply with an air of calm, but inside, my heart is pounding like crazy as another adrenaline rush kicks in. I am excited, thrilled, prepared, and in shock. I am ready for anything.

The van continues its wobbly way up Amsterdam Avenue into Harlem, where police say a man is holding a machete to his three-year-old son’s throat, threatening to kill the terrified child unless the city’s Social Services Department restores him custody of his son and four other children. The agency reportedly took the kids after the man was ruled unfit to raise them. Officials say he became delusional after his wife was killed in a recent arson fire, and he was left to raise their five children alone. The weight of all the mounting family pressures clearly took its toll on the man, as well as a disastrous turn for his offspring.

As I stare out the window, wondering what in the world could drive someone to such madness, I feel my own growing anger at the thought of someone taking my loved one away. I imagine holding a machete to Eve’s throat as she tearfully begs for mercy—if what I most fear is true. I am somewhat glad this big hostage story broke now, granting me at least a bit more time to think about what I am going to say to Garrett.

Do I just come right out and say what I suspect to be true—that my husband is fucking my best friend? Or should I wait for more evidence? Ha! More evidence? How much more evidence do I need? Does God have to draw me a picture before I finally realize what even Ray Charles can see? I must be an idiot not to have noticed—or to have pretended not to. There comes a time in every woman’s life when she has to be truthful to the things she is pretending not to know. That time has apparently come for me.

I must now admit the horrible truth: that somewhere deep down inside, I have always known there is far more than just an innocent friendship between my husband and my best friend. They grin in my face as they smile at each other, laughing about old times and how they go so far back that they consider each other as brother and sister.

I shudder as I remember how many times I thought I caught a glimpse of some far deeper familiarity and knowing between them. It made me feel insecure and uncomfortable. Did I see what I think I saw, or am I imagining things? Is this betrayal drama playing out only in my head? I saw the way their hands brushed that day as Eve joined us in our kitchen to help us prepare for a party. I see the mysterious way their spirits seem to commingle—and so naturally. I can actually feel the energy and heat between them, and whenever Eve is with us, I often feel like an outsider in my own home.

I see a touch here, or a too-long lingering smile there, or that surprising and way-too-thoughtful gift that Eve gave Garrett last Christmas. It was a dull beige pullover sweater that on any other day, or from anybody else, would have surely been a return or regifting item, but Garrett cherished that damn sweater from Eve as if she had woven it herself with strands of gold. But it wasn’t gold; it was a drab beige sweater, and I hated it as it sat there all stunningly hand-wrapped, right under my nose, right under our Christmas tree. Garrett’s eyes lit up when he read the gift card: “To Santa—From Eve.”

“Wow, this is beautiful!” he exclaimed like an excited little boy that bright Christmas morning. The big gold satin and mesh bows on Eve’s gift had little nutcracker soldiers entwined in them. Sweet little keepsakes for Christmases to come, we thought.

“Cool sweater.” Garrett rubbed the wool. “It’s an Eddie Bauer.”

“Well, that was nice.” And while I put it off, one of my mother’s warnings started clanging loudly in my head: “Respectable women don’t give men clothing as gifts; it’s far too personal.”

“Give him something for his desk or a good book to read,” Mother had suggested. “Clothes imply intimacy.”

I thought my mother was nuts—until that Christmas morning as I watched my husband smiling from ear to ear over another woman’s gift of a wheat-colored sweater that he would wrap himself in just about every other day. This, to me, was a fleeting but strong sign that my mother might be right.

I hated that damn sweater.

And then, just this week, I get this urgent and awkward call from my hairdresser, Maxine Johnson, who also styles Eve’s hair. Maxine, a gruff ghetto girl who snaps gum while she back-curls and blow-dries hair, asks if I could stop by her apartment after work sometime this week because she has something very important that she needs to talk to me about concerning Garrett, and it can’t wait. Maxine’s tone sounded so severe that out of concern, I asked if everything was all right. She told me she’d feel a lot better if we could speak in person—and the sooner the better. She also made me promise not to mention our meeting to Eve or Garrett. She spewed out her address and abruptly hung up the phone. I found her phone call odd but figured it must be something awfully urgent for her to sound so strange.

After work, I caught a cab down to the Chelsea projects and made my way to Maxine’s apartment, past some old men talking smack a

nd laughing loudly over a game of dominoes.

As I passed a group of youngbloods hanging out on a park bench, listening to rap music, one of them yelled out in my direction, “Hey, ain’tchu that news lady?”

I nodded my head and kept stepping toward Maxine’s building, cautious but happy that these homeboys were at least watching the news.

“Whatchu doin’ down here?” They guffawed.

“Just seeing a friend,” I shouted back over my shoulder as I also picked up my pace. “Just seeing a friend.”

“I’ll be your friend!” one of the youngbloods said, flirting. “I wanna date the news lady!”

The boys burst into cackles of laughter, busting chops and slapping fives.

But it seemed my friend Maxine was the one delivering the breaking news that day.

I finally entered her building, darted into the big clunky elevator, and pushed the button to the nineteenth floor. The elevator car smelled like piss, and I wondered why anyone would pee in their own elevator.

When I got to Maxine’s nineteenth-floor apartment, she seemed relieved to see me. “Come on in, girl,” she said. “Rushion, get your stuff, and go on in your room now.” Rushion is Maxine’s lazy-ass seventeen-year-old son who still cannot read. He made a disgruntled face, mumbled something under his breath, scratched his fat stomach, and slowly headed back to his room, where he slammed the door.

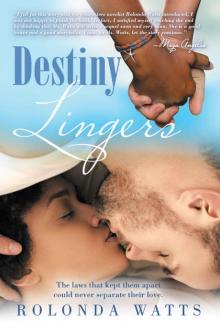

Destiny Lingers

Destiny Lingers